Ever since the first Ultimate Fighting Championship event in 1993, part of the inherent allure of mixed martial arts has been rooting for the underdog. This is not endemic to MMA—it goes back at least a few thousand years to David flinging pebbles at Goliath—but it is built into it in ways that are prevalent. Thanks to Royce Gracie’s scrawny feats of badassery, no other sport is as organically defined by smaller competitors defeating bigger ones.

However, cheering for the underdog is not solely a matter of betting odds, though that is its most obvious manifestation. To my mind, cheering for the underdog means cheering for the fighters of whom less is expected, the fighters who elicit less fanfare and attention in the run-up to the fight. The underdog-house, so to speak, is more commonly known as the undercard. The further down on the card you go, the bigger the underdog.

This expanded definition is not just a result of my affinity for the term “underdog-house,” fun as it is. There is also a demonstrable justification for it. Not only do the low-rung fighters typically make a literal fraction of what the headliners make, but they also get a lot less performance bonus love. For the Average Joes on the rise, that extra $50,000 is both a substantial multiplication of their fight purse and a perpetually unreachable achievement…

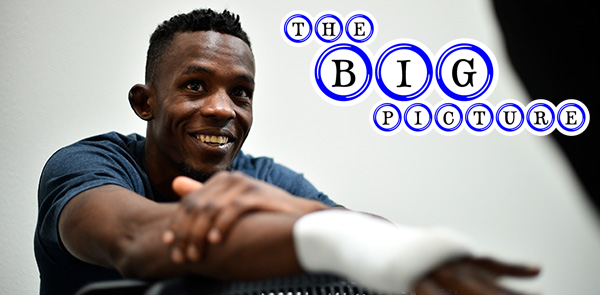

Like